UPDATE 1 : I received a notification from David Sibley himself! “"I can say right now to assure you that we are committed to updating and improving the app going forward.” So because of that I’m saying that you should purchase this app now, especially if you are reading it while it is at the discounted price of $9.99. Sibley assures the issues will be fixed soon!

UPDATE 2: I received an update to my iPhone app on November 22 and many of the problems pointed out in this review have been addressed. It appears emailing errors you find in the app can be addressed relatively quickly.

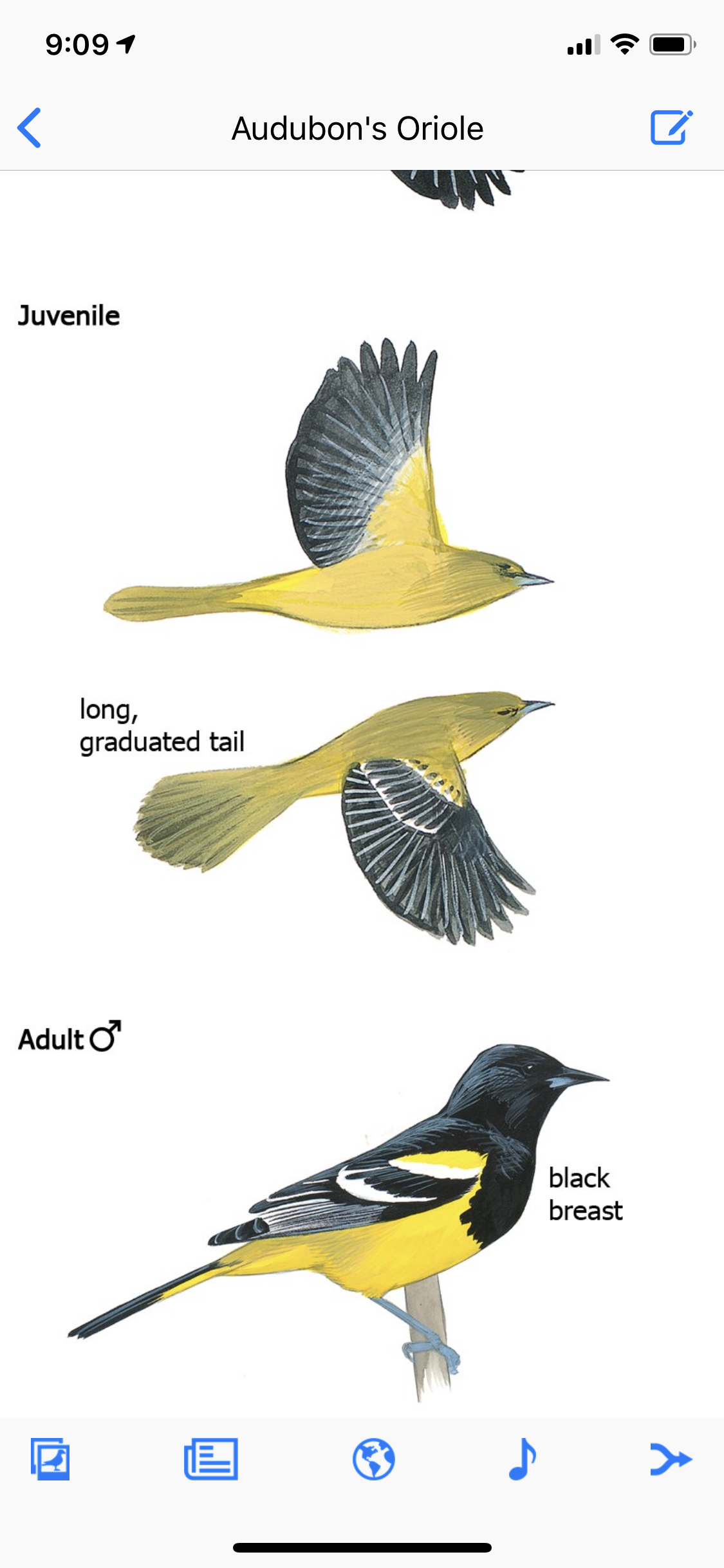

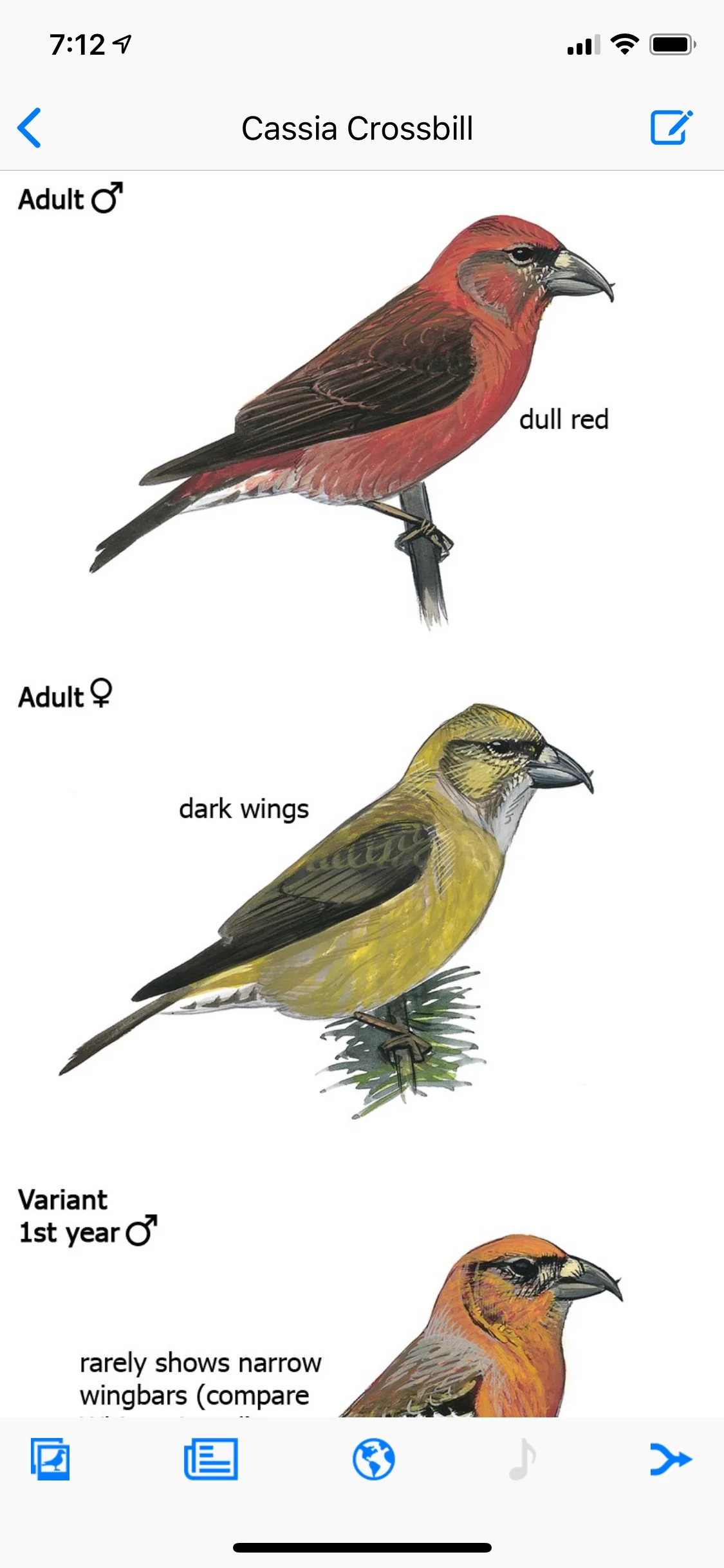

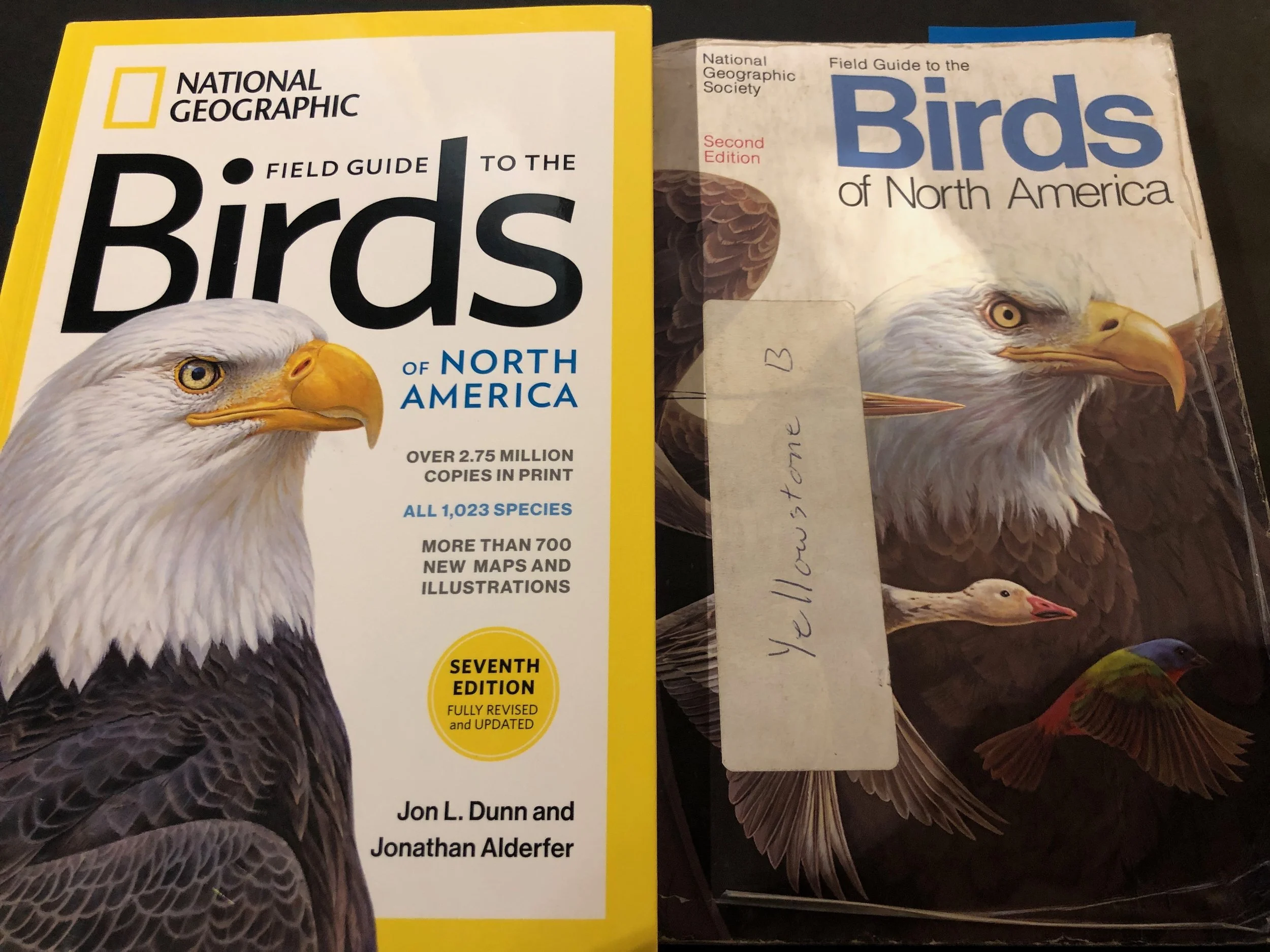

Poor David Sibley. He is an amazing artist who has gifted us with a revolutionary field guide. His publishers keep getting in the way of his outstanding art.

So…should you buy the Second Edition Sibley app? I honestly don’t know. UPDATED: YES!

Currently the app is in the iTunes store for $9.99. Word on the street is the price will go up in a month to either $19.99 to $29.99. Presumably they will fix these problems so getting it at a discount now is a good deal…though if they don’t…well…it’s a waste of money.

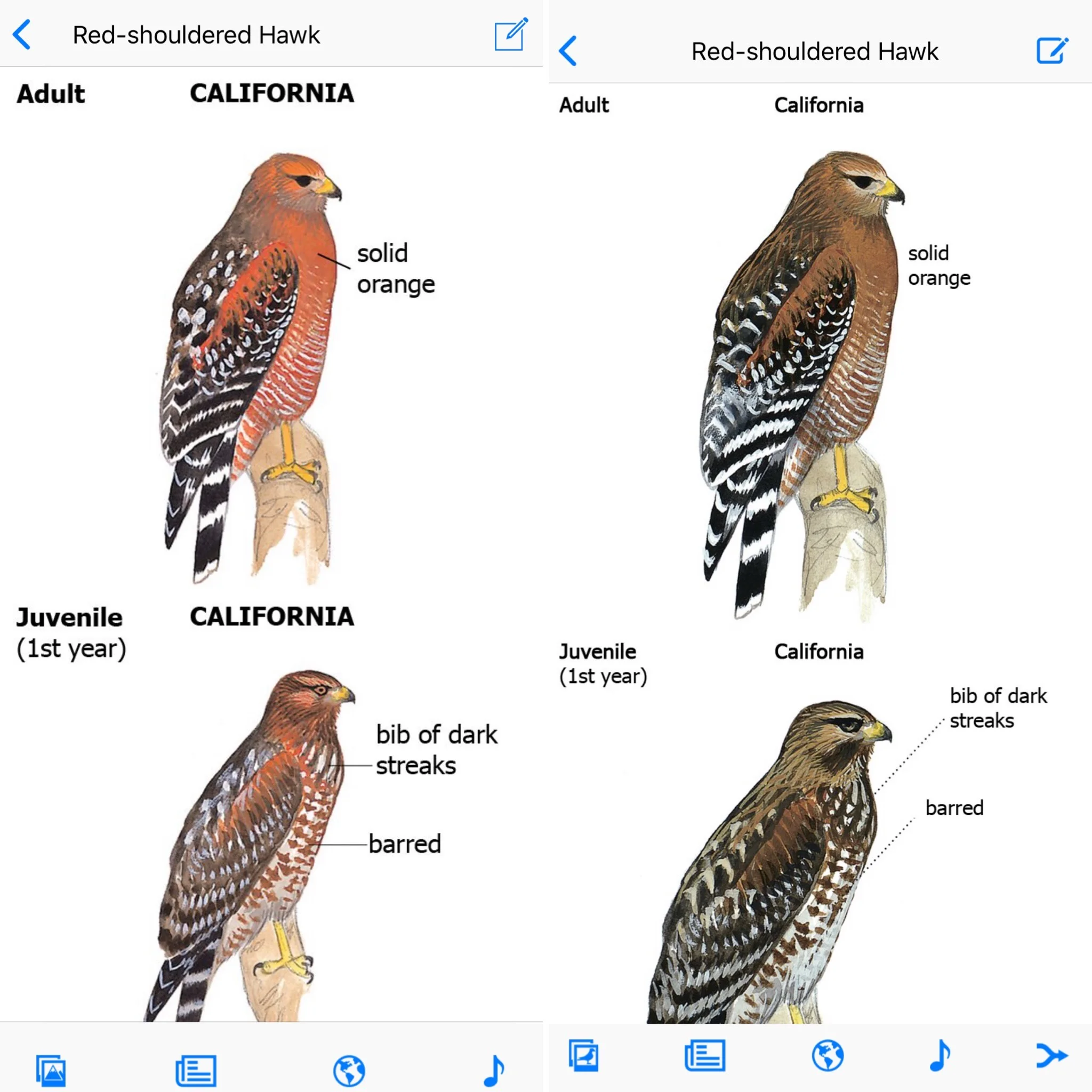

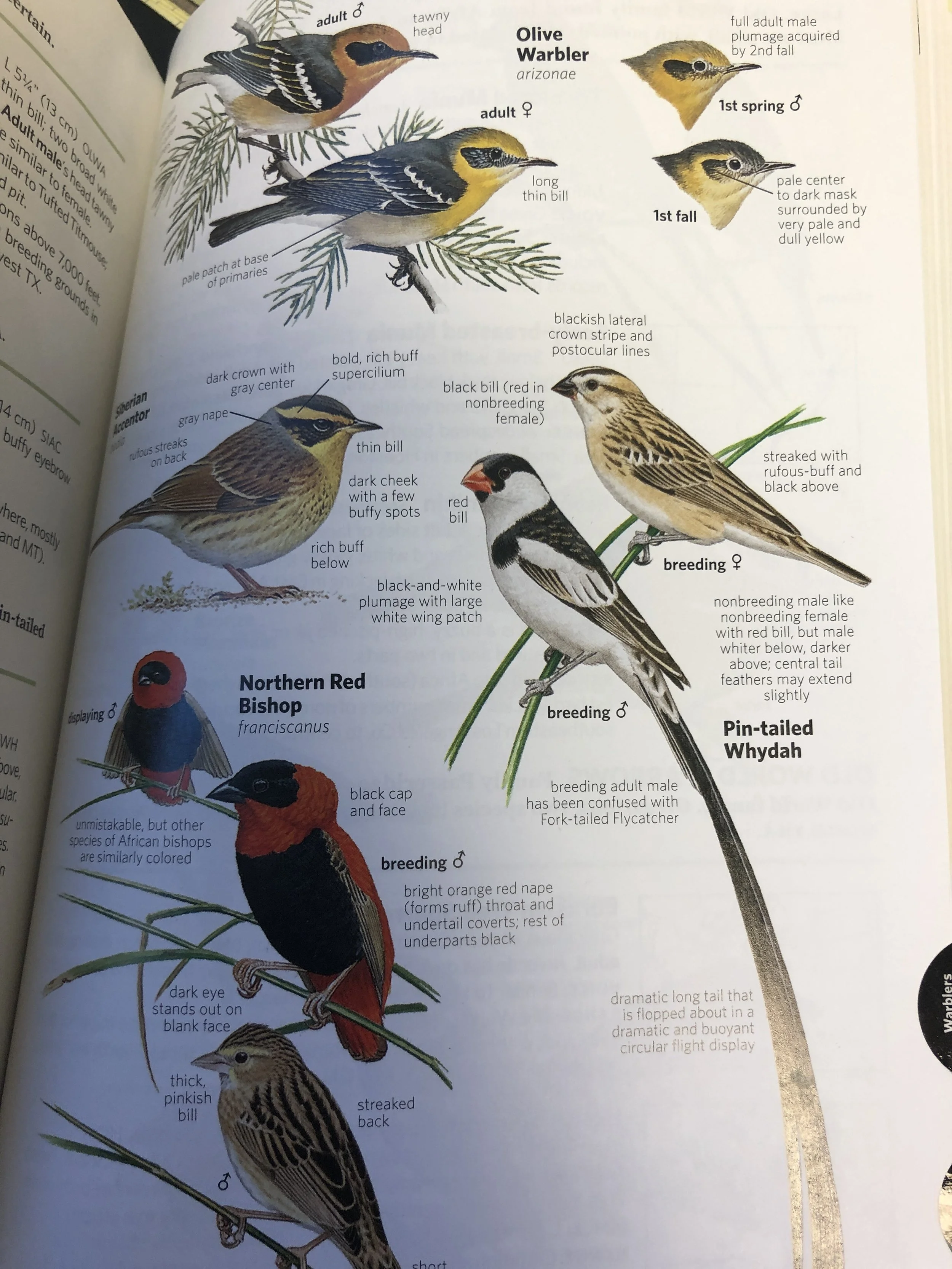

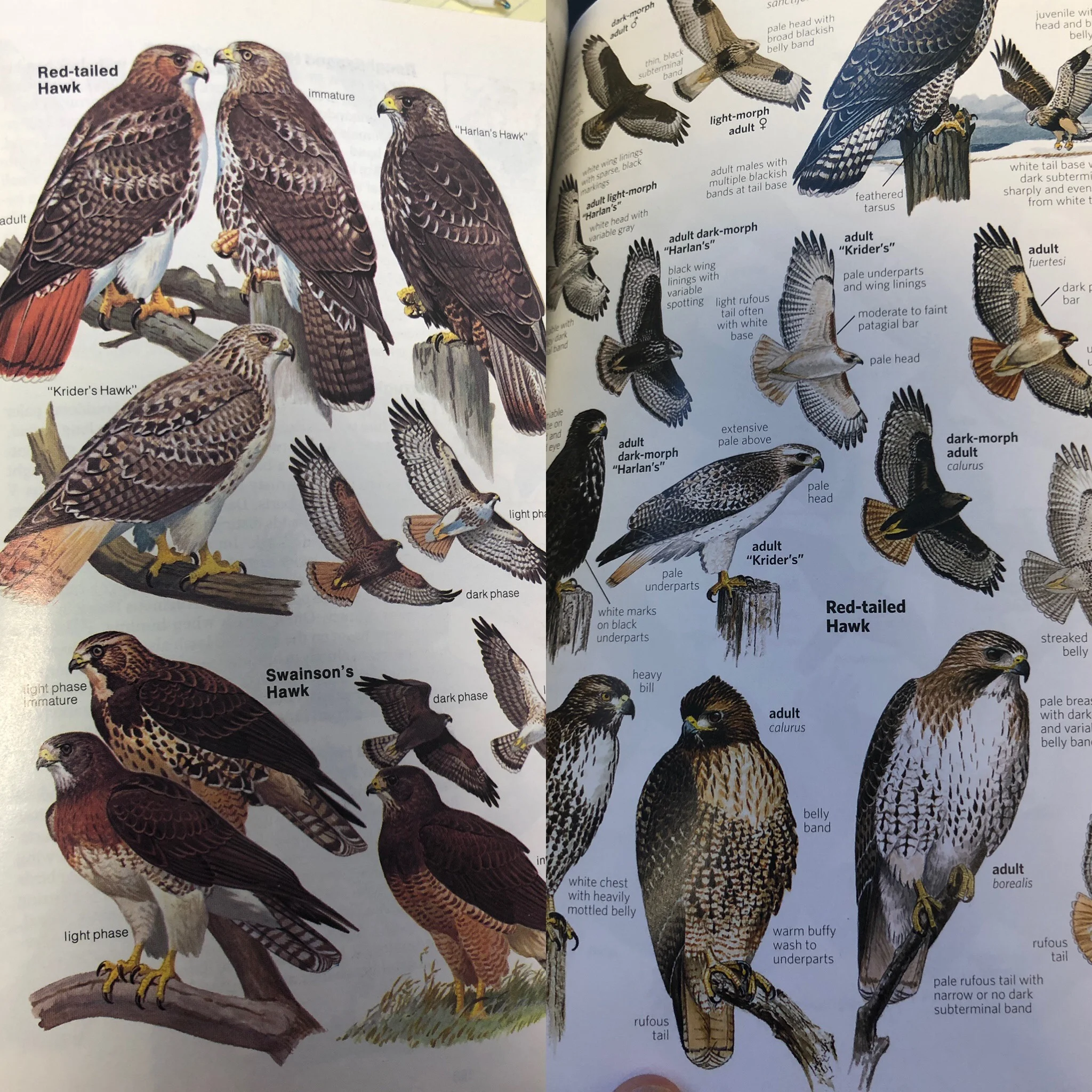

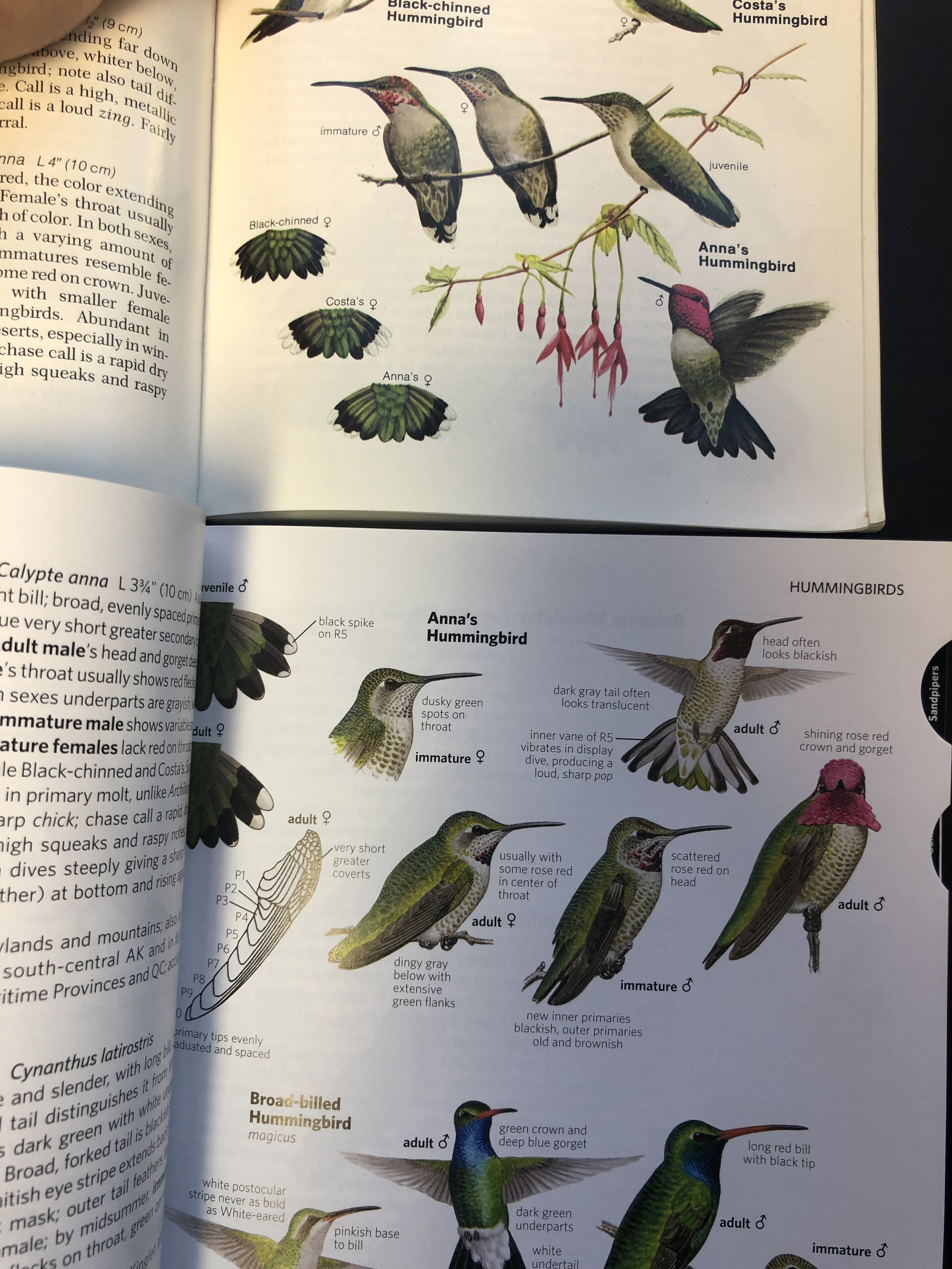

For years birders have been waiting for either an update or new Sibley app when his second edition came out in 2014. When that second edition Sibley came out there was a printing problem. Many of the birds were darker than they should be and the font was not great for older readers. This led to a recall and a second printing. Birders love the Sibley Guide and so have been anxiously awaiting the second edition in app form only to be told that it would be coming “soon.”

Finally, we all got updates in our Sibley apps on Friday directing us to an “update” which was a link to buy the 2nd edition. So I paid the $9.99 and downloaded it. I have a ritual for field guides where I look at my favorite bird pages first (don’t we all). One of those is the scarlet tanager. I especially wanted to check that because it was such a problem with that second edition first printing. I gasped and thought, “Oh no, they wouldn’t have been that foolish.”